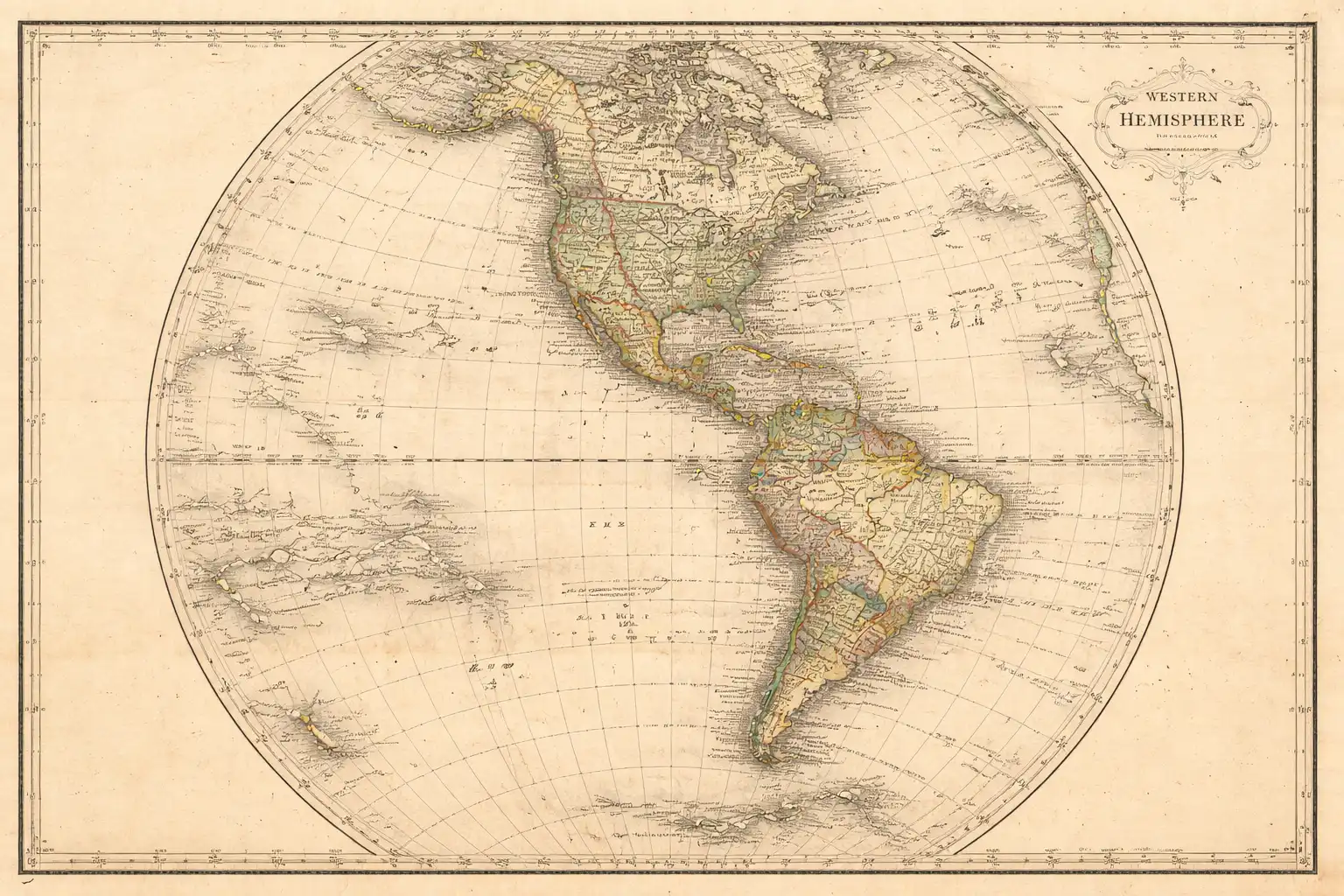

Washington, DC, USA - On December 2, 1823, President James Monroe delivered his annual message to Congress and planted a marker that would echo for two centuries: the Western Hemisphere was not to be treated as open terrain for new European colonization, and attempts to extend European political systems into the Americas would be regarded as dangerous to U.S. peace and safety.

It’s tempting to treat the Monroe Doctrine as either a relic or a blunt instrument—something the modern world should have outgrown. But the historical record tells a different story. The doctrine did not follow a straight line from declaration to application. It behaved more like a tide: asserted, expanded, constrained, submerged, rebranded, avoided, and then—under pressure—brought forward again.

To understand why it keeps resurfacing, it helps to look at how it was used, and just as importantly, when it was not used—or when leaders chose to speak in different language while still grappling with the same underlying realities: proximity, power, outside influence, and instability in the neighborhood.

The original Monroe Doctrine is often remembered as a sweeping claim of hemispheric authority. In its earliest form, it reads more like a strategic warning than a detailed policy: European powers should not attempt new colonial ventures in the Americas; the U.S. would not interfere in existing colonies; and the U.S. would largely stay out of European affairs.

What mattered most was the boundary it implied: the Americas were developing their own political order, and Europe should not reverse it. That framing made sense in a world where European empires still had both the habit and the capacity to intervene.

For decades, the doctrine lived more as a principle than as a routine operational tool. It was referenced, but not consistently “enforced” as a doctrine of day-to-day management.

The most dramatic transformation came in the early 20th century—when the U.S. began interpreting regional instability as an opening for outside intervention (especially by European creditors), and then positioning itself as the alternative.

In 1904, President Theodore Roosevelt explicitly tied the Monroe Doctrine to a new rationale: in “flagrant” cases of wrongdoing or impotence in the hemisphere, the U.S. might be forced—however reluctantly—to exercise an “international police power.”

This is the pivot that made the Monroe Doctrine feel, to many, less like a shield against empire and more like a framework for stability-by-intervention.

Whether one sees that shift as inevitable, opportunistic, or strategic, it is historically central: the doctrine’s meaning expanded from “no European colonization” to “U.S. responsibility to prevent conditions that invite outside involvement.”

And once that door opens, “intervention” becomes an argument about necessity, not preference.

By the 1930s, there was a visible effort to step away from the interventionist pattern that had become associated with the corollary era.

Under President Franklin D. Roosevelt, the U.S. advanced the Good Neighbor Policy, emphasizing sovereign equality and a turn away from armed intervention. In his 1933 inaugural address, Roosevelt framed the ideal “good neighbor” as one who respects the rights of others and the sanctity of agreements.

Importantly, this was not the Monroe Doctrine being repealed. It was something subtler and more telling: the doctrine was being culturally and diplomatically reinterpreted. The hemisphere would still matter, but the preferred mechanism would shift toward reciprocity, diplomacy, and (eventually) collective security.

This “pushback” phase became part of the story’s rhythm: the doctrine is not just used—it is also softened when the costs of unilateral enforcement become too visible.

After World War II, hemispheric relations increasingly leaned on multilateral institutions and principles. The Charter of the Organization of American States (OAS) includes strong non-intervention language—stating that no state or group of states has the right to intervene directly or indirectly in the affairs of another.

This is a crucial development for the Monroe Doctrine’s lifecycle.

It doesn’t erase the underlying strategic logic of proximity and external influence—but it changes the vocabulary and the legitimacy structure around action. “The hemisphere matters” becomes less likely to be said as “the Monroe Doctrine,” and more likely to be said as:

In other words: the doctrine’s logic can persist even when the doctrine’s name recedes.

During the Cold War, the U.S. often acted forcefully in the hemisphere—but the dominant justification was usually containment rather than Monroe per se. The problem being addressed was framed as global ideological competition, not primarily European colonialism.

This period is one reason the Monroe Doctrine feels “dormant” in memory: the U.S. could pursue hemispheric primacy while speaking in a different dialect—anti-communism, proxy conflict, and security alignment.

After the Cold War, the Monroe Doctrine increasingly took on the feel of a historical artifact—less because it was formally renounced, and more because the prevailing worldview shifted toward:

In this era, the doctrine became something many diplomats preferred not to invoke—because naming it revived associations with paternalism and interventionism.

The result: the Monroe Doctrine didn’t vanish; it became unsaid.

The most direct modern attempt to close the book came in 2013, when Secretary of State John Kerry declared at the OAS that “the era of the Monroe Doctrine is over.”

That line is notable precisely because it treats the doctrine as a named era—something the U.S. could decide to exit.

But even that statement did not end debate. Commentary at the time suggested that, from a Latin American perspective, the gap between rhetoric and reality would be what mattered.

And in a deeper sense, Kerry’s line illustrates the Monroe Doctrine’s unusual status: it is not merely a policy; it is a symbol. Calling it “over” was as much about tone and relationship as about strategy.

By the late 2010s, the doctrine’s name began to resurface in U.S. discourse—often tied to concerns about Chinese and Russian influence and to crises involving authoritarian regimes and sanctions in the region.

A useful snapshot is the Trump-era framing of authoritarian states in the hemisphere and the insistence that the region is a special strategic zone.

Around the same time, reporting noted debate over whether U.S. officials were effectively praising or reviving Monroe-style thinking in response to China’s growing economic footprint.

This is the doctrine’s “return” pattern: not necessarily as a formal doctrine, but as a convenient shorthand when officials want to say some version of:

In the present moment, the Monroe Doctrine’s name has clearly re-entered public conversation, especially in the context of Venezuela and broader Western Hemisphere security framing in early 2026 reporting and commentary.

Whether one agrees or disagrees with any given policy response, the historical point is this:

The doctrine tends to re-emerge when three conditions converge:

That combination compresses time. Suddenly 1823 doesn’t feel like ancient parchment; it feels like a reusable argument template.

If the Monroe Doctrine is returning as a named reference point, the hemisphere may be entering a period defined by an unresolved tension:

This is the Good Neighbor / OAS spirit:

This is the doctrine’s revived gravity:

Neither vision completely eliminates the other. That’s the subtlety of the last century: the hemisphere oscillates between them depending on threat perception, domestic politics, and the global balance of power.

One plausible forecast is that the Monroe Doctrine will function increasingly as an implicit operating principle—less as a banner, more as a posture:

In that future, the argument won’t be “Monroe Doctrine”—it will be “resilience,” “security,” “stability,” “organized crime,” “energy,” and “external influence.”

But the structural claim underneath will rhyme with 1823:

the hemisphere is not neutral terrain.

The Monroe Doctrine’s real story isn’t that it was good or bad. It’s that it has behaved like a historical muscle—tightening when the body senses danger, relaxing when the danger fades, and sometimes tightening again long after people thought the reflex had disappeared.