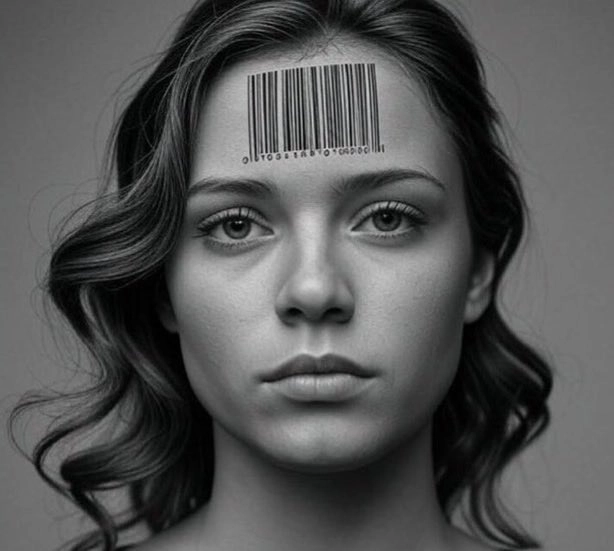

London, England, UK - Governments around the world are exploring two controversial technologies: Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs) and Digital IDs. Supporters say they’re the next logical step in efficiency — a way to modernize money and identity for the digital age. Critics see them as surveillance tools that could concentrate unprecedented control in the hands of central authorities.

Both views have merit. Both also depend heavily on trust.

Proponents make a clear argument:

From a technical standpoint, these systems promise speed, precision, and clarity. The Bank of England, European Central Bank, and others all argue that modernization is inevitable; it’s just a matter of doing it safely.

Skeptics don’t necessarily oppose innovation — they oppose centralization. Their warnings fall into several key themes:

In this view, CBDCs and Digital IDs are less about modernization than management — the “upgrade” that quietly changes who holds the keys.

Even among experts, there’s room for nuance.

In practice, every country will land somewhere along that spectrum.

Here’s the crux: these systems only gain power if citizens consent — actively or by apathy.

Governments can design frameworks, but they can’t force trust. If people reject or abandon digital systems that feel invasive, the systems collapse under their own weight.

History shows this again and again: societies ultimately go where citizens allow them to go.

The technology may start in the hands of central bankers or bureaucrats, but its permanence depends on public acceptance — on whether ordinary people see it as useful or dangerous.

Even the most ambitious governments are rarely as efficient or coordinated as people fear. Bureaucracies are slow, fragmented, and often clumsy. They can propose sweeping programs but struggle to implement them coherently. That limitation, while frustrating, is also a hidden protection — a reminder that the “controllers of finance” are not all-powerful, and their reach depends on how much room we give them.

Both will coexist for a time. The question is which vision the public rewards.

Every generation decides how much freedom it wants to trade for convenience.

If people insist on transparency, privacy, and limited government, technology can serve them.

If they remain passive, the same tools will be used to manage them.

The future, in the end, isn’t decided in central banks or ministries.

It’s decided by citizens — in what they accept, what they reject, and what they’re willing to protect.